Words by Joel Lewin, Art by Rhys James.

In the last days of my addiction I accumulated two socks full of coins. I didn’t know how much these socks and their contents were worth but I had high hopes. They were heavy. They were noisy. They were fat. Everything you would look for in a coin-filled sock.

Money is a metaphor, and these socks represented much more than the value of their contents. These socks were the deeply satisfying goodbye high that would allow me to draw a line under my addiction and never go back.

As I walked through Kings Cross I could feel the socks in my bag, thumping my flank. I could hear them jingling. I could feel the flutterings of anticipation of what I was about to do with them.

The thing about these socks is they were filled with coins of multiple currencies. But that wasn’t a problem, for in London we have these sophisticated machines. They transform metal into paper, and unusable alien currencies into valuable British pounds. You just put the metal in and out comes the paper. Nobody knows how they do it because nobody’s ever seen inside one.

I siphoned the coins from the socks into the tray with no little excitement. As I decanted, the digits racked up, topping £120. This was more than enough for an itch-scratching goodbye to heroin.

But the moment I cashed out I knew something wasn’t right. An ominous rattling. And instead of a thin crisp stack of paper this supposedly state-of-the-art alchemy machine squirted out a stream of copper.

I watched in horror. The coins kept coming.

I was only jerked out of my paralysis when the tray overflowed. Started refilling the socks. When the machine had disgorged I stared at it some more. Exchanged a few angry words. Pushed some buttons.

I walked away with two even heavier socks of far less value.

Once I’d found a newsagent willing to exchange, and more importantly count, these sock sacks of coins, I was left with ~£40 and a sense of burning injustice. This would barely keep me well for the day let alone high.

And so, like, most addicts I know, I was left with the bitter taste of disappointment after my last hit. Is that all? Unfortunately I had someone to blame for this- the machine.

I can’t get clean because of that machine

For the next month and more as I detoxed I fixated on that machine. He had deprived me of the quenching last hit I felt needed to draw a line under my addiction and move on.

I was stuck in this delirious reason-resistant mania that characterises early recovery for many addicts.

That obsession is underpinned by craving. During addiction your brain gets sensitised to certain cues that it associates with drugs. These cues can be people, places, things, feelings… credit cards, spoons, bottles, sunny days, sickness, euphoria, Rodney from up the road… The longer you use the more cues you accumulate. A glimpse of a well-endowed bicep vein. Even words… breathe…flush.

And then the night when you finally fall asleep you dream of drugs and wake up just before you push down on the plunger or snort the line.

All roads lead to Rome.

When you perceive the cue dopamine floods up from the midbrain into the accumbens and ignites a burning desire for the drug. It screams: “I want it… I need it!” It feels like that drug is crucial to your survival.

“Just. One. Last. Time.” And then I’d think of the machine… “I can’t get clean because of that machine.”

Gold Fever

“I see this little look in an ex-heroin addict’s eyes. It kind of reminds me of gold fever,” says Luke Richardson, a therapist.

“There were a couple of gold rushes in Australia in the 1800s, and they had the gold fever or the gold rush, because someone found a nugget in a particular area and out they came.”

“I think it was similar to the American gold rush, in that you claimed a patch of land and then you could dig down as far as you wanted in any direction. You could do what you like. So it was really dangerous and they could die but they could also find a nugget, and be rich forever.”

“It reminds me of that gold fever, which also reminds me of a gambler chasing a win, that starstruck kind of look, that just says, “I want it, and I’m just gonna look for it til I get it, and I’m pretty sure I’m gonna get it, and it’s like a buzzy, “It’s miiine,” not like a, “My preciooussss,” not like a clingy sort of grasp, but a very determined “I’ll have that” kind of grasp or gaze.”

A great disinclination to reading the Bible

An 1849 New Zealand periodical, The New Zealand Evangelist, tried to make sense of the “slightly alarming symptoms of a new disease” ravaging the country: gold fever.

The progression of this disease bares a striking resemblance to the trajectory of addiction; delight to dereliction:

“The symptoms of this fever are, at first a peculiar sensation about the heart, sometimes a slight headache, great restlessness during the day, and an inability to prosecute the ordinary business of life; a great disinclination to the reading of the Bible, to secret and family prayer, and even to public worship; and at night the sleep is much broken by incoherent dreams.”

“In a few days a slight delirium comes on; fairy landscapes and enchanted castles rise up in bright and endless perspective before the mind, and like the first stages of delirium in other fevers, it is a highly pleasurable state of existence; the patient fancies that the golden age is returned, that he himself is another Midas, that he has discovered the philosopher’s stone, and by its subtle alchymy he can turn everything it touches into gold.”

“If the disease increases, and the fever runs its course, the patient becomes quite unmanageable and raves continually about El Dorado and California, and unless he is restrained by main force, will throw away his property for half its value, abandon his business, his prospects, his friends, his religion, and risk health, life and heaven;—will brave seas, storms, pirates, famine, banditti, murderers, and all the dangers of a foreign, uncultivated land, destitute alike of law and gospel, for the doubtful chance of a few ingots of gold.”

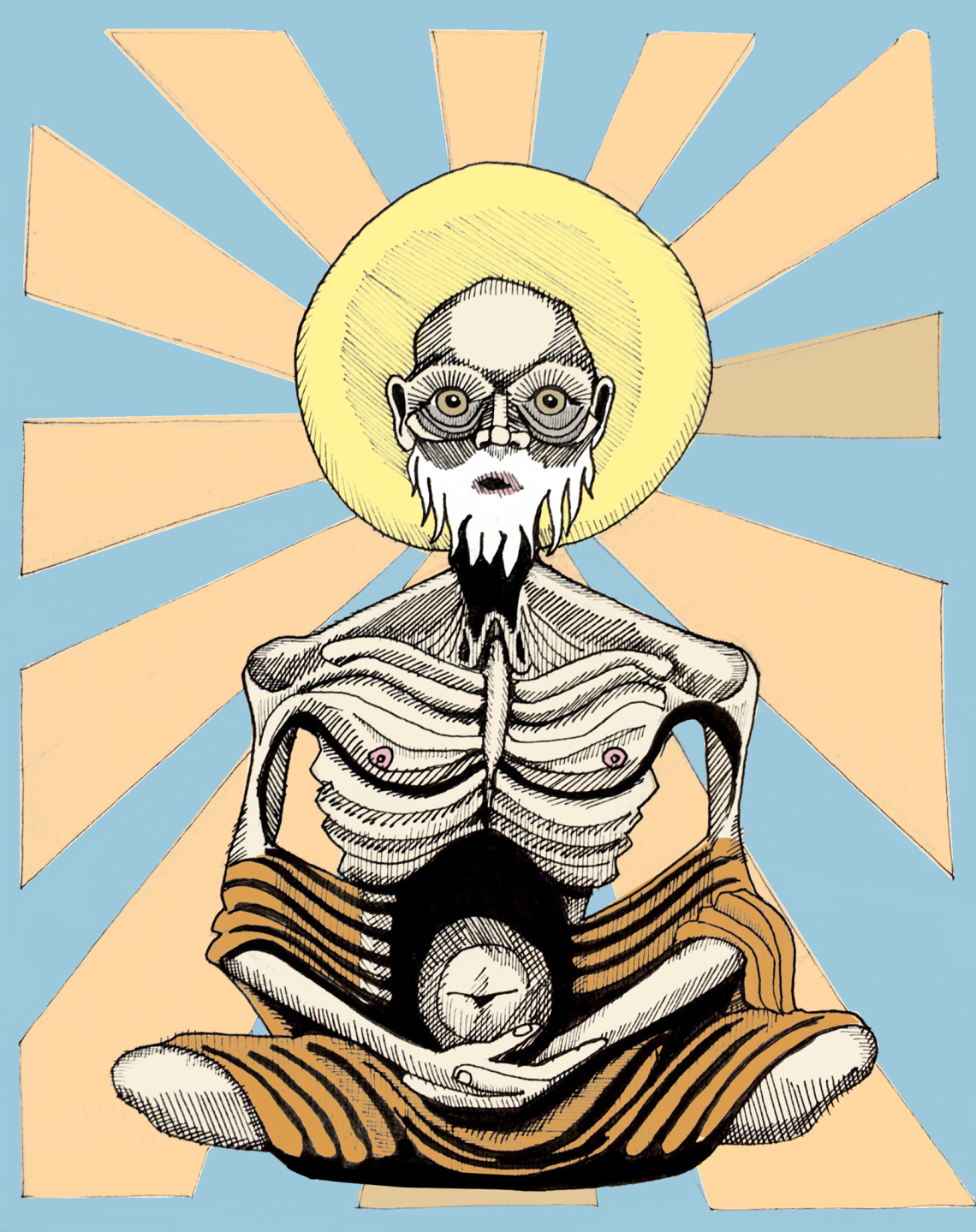

“The sequelæ of the fever is frightful spiritual emaciation, and hence a universal condition there is leanness of soul.”

“Leanness of soul”… what a phrase. Sounds familiar. It comes from a verse in the Bible where God gives the Israelites abundant bread but they ask for meat as well. He gives them what they wanted, but throws a plague in too.

Gold fever… Different substance. Same shit. And I’ve seen similar obsessive, feverish symptoms induced by gambling, gaming, Ebay… Tinder addicts compulsively swiping all night to the detriment of everything else, mining for that golden match.

What is it about human nature that makes us eternally susceptible to these all-consuming feverous obsessions?

Insatiable craving machines

The thing is, if that Kings Cross machine had doubled or even tripled my money the outcome would have been the same. Disappointment and craving. Because the problem wasn’t that machine. The problem was this one.

Human beings are essentially insatiable craving machines. That’s the way our brains are built.

In the 1990s Ken Berridge, a psychology professor at the University of Michigan, stumbled upon a revolutionary discovery. At that time it was received wisdom that dopamine creates pleasure. But in an experiment with rats he discovered dopamine is not about pleasure. It’s about desire.

“In the 1990s, it was a lonely scientific position to maintain that dopamine didn’t mediate pleasure,” wrote poor ole Berridge.

Over the following decades Berridge developed this theory into what is now widely accepted: wanting and liking are two distinct and separable processes. We can want something without liking it, and we can like something without wanting it.

What really matters here is this:

The brain’s wanting systems are much more substantial than it’s liking systems.

Whereas ‘wanting’ is “generated by large and robust neural systems”, Berridge and his colleague Terry Robinson have explained:

“The pleasure-generating hotspots are anatomically tiny, neurochemically restricted, and easily disrupted – perhaps a reason why intense pleasures are relatively few and far between in life compared to intense desires.”

And that’s not just addicts. That’s everyone.

According to their theory, as an addiction progresses, there is an amplification of wanting with no amplification of liking. So addicts want their drug more but like it less.

It’s a fairly excruciating cycle of craving and disappointment… craving and disappointment.

The fact dopamine mediates not pleasure but desire explains why, for gambling addicts, the addiction is about the pursuit of a win rather than the win itself. Hence why they often continue the pursuit even after they’ve got what they were pursuing.

Berridge and Robinson distinguish between cognitive wanting and a more visceral wanting, which can occur in opposition.

As any addict knows, you can want it without wanting it. You know it’s the worst thing you could do but it’s the only thing you want to do.

Nirvana

“You know that old saying, “You’re just trying to chase that original high, trying to relive that beautiful first moment,” says Richardson.

“I kind of get that with heroin addicts, because I think, in my personal opinion, the people who get addicted to heroin, are the ones that it’s like an answer for. It fills in that missing piece, and so their original high of heroin is like “yesss I’ve spent my whole life searching the planet for this moment.”

“I kind of get this feeling it’s like a nirvana, that for people who are addicted to heroin it becomes a major goal in their life- they want that nirvana, or “oblivion” as I’ve heard one addict say it. And they feel like if. ‘I get a big enough hit then I’ll go into nirvana for long enough that I’ll be able to keep a piece of it, I’ll be able to bring a little bit back home.’”

“I’ve just heard it from so many different people, from so many different backgrounds.”

In Buddhism Nirvana is a state of liberation from the cycle of rebirth and suffering. It comes from the Sanskrit vāna meaning “blown” and nis meaning “out”- blown out or extinguished.

That resonates with what was a desire to extinguish my addiction with a valedictory snowball. To liberate myself from the endless cycle of death and rebirth that comes with the sick-high cycle.

And it certainly felt like I hadn’t blown hard enough…. Because of that machine.

So what can we do?

It’s interesting that Richardson mentions Nirvana. Heroin (and other drugs) offer an illusory path there. It gives you a taste of something you will never get enough of.

Having unearthed the neural mechanisms underlying this insatiable thirst, Berridge has also honed in on Buddhist practices as offering a solution.

And it makes sense. Thousands of years ago the Buddha identified insatiable craving as the cause of suffering, and mapped out a practical path of liberation.

This path is occupying an increasingly prominent place in the recovery landscape.

As the Buddhist recovery group, Recovery Dharma, write in their literature:

“Addiction itself increases our suffering by creating a hope that both pleasure and escape can be permanent.”

“It is possible to end our suffering. When we come to understand the nature of our craving and realize that all our experiences are temporary by nature, we can begin a more skillful way to live with the dissatisfaction that is part of being human.”

And best of all this path doesn’t depend on machines in Kings Cross.

Or if you like the kiwi Evangelists best, you could try the affirmations which they prescribed as a cure for gold fever:

“He that loveth silver shall not be satisfied with silver.”

“Riches make to themselves wings and fly away.”

“How much better is it to get wisdom than gold?”

Insert your drug of choice and write them on your mirror…

Hey Joel: I’ve worked at the FT for 40 years and I’d like to email you about something addiction-and-FT-related, privately. I’ll be retiring at the end of December, but until then my FT email will still work. Or you can google me and you’ll see I really am who I say I am. My ft email is patti.waldmeir@ft.com, my private email is below. Keep up your great writing!

LikeLike

You are a talented writer. This article really pulled me in. Nice work. My daughter has this talent as well. She truly needs to hone-in on her skill—but she is a natural. I would love to send her this article, but alas, she also had a pretty ferocious heroin problem and I don’t know if this would be an appropriate article for a mom to send to her recovering daughter. What do you think? Do you have any other examples of your writing (not drug-related)? Thx!

LikeLike