I was at a wedding in Mexico. Fun. Sun. Boats. Pre-Aztec canals. A Jewish chuppah. Some kind of water coming out of some eyes, including mine. Stamping on a glass. Cheering. Several kinds of happiness. Then the dancing started.

I have done many things in recovery that I did not believe possible without chemicals. Work. Talking to humans. Speaking to large groups of humans. Having fun. Tolerating sadness. But after six years, one thing remained impossible sober: dancing.

Once upon a time I used to enjoy it. But to get to a place where this was possible was messy. To cease being cripplingly self-conscious of my body, I had to lose touch with the notion that I had one. If I retained the concept of ‘arm’, I remained self conscious of my arms. It was only when they became mysterious raw sausages flopping about near me, but not me, that they could move freely.

Since I stopped using drugs six years ago, I had tried to dance. I had dragged myself onto dancefloors at weddings to be polite. I shuffled about, painfully aware that I had both arms and legs and that they ought to be doing something but instead of just getting on with doing that something they were all asking me what that something was. If the left arm went up in the air the right arm would ask, “But what about me? We can’t both be up there at once, but I’m not just gonna stay down here either.”

So I’d thrust him out in front of me. And then I’d see someone’s eyes pointed in my general direction and I’d ask myself on behalf of those eyes, “What the fuck are you doing?” And all this was quite baffling so I’d put myself out of my misery and get off the dancefloor.

But this wedding in Mexico was different. There were old friends and new friends and two dear friends having the day of their lives. There was exuberance. And at last I crossed the final frontier. I drank some water and went to the dance floor.

At first the limbs were asking their usual questions. I answered them patiently. Right arm, go out to the side and jiggle. Left arm, you twirl over head. But as I was confronted by a growing awareness that the people around me were not the only ones having fun- that I was too- the questions stopped coming and the limbs just did their thing. I had broken through into a new plane of consciousness. When eyes came my way I no longer asked, “What the fuck am I doing?” Nobody cared what I was doing with my limbs. Everybody was busy enjoying themselves. Or so I thought.

Sometime after this psychic revolution, a man, not young, not old, not dancing, but not entirely not dancing, just shifting around at the edge of the dancefloor, shuffled towards me and said in my ear, “Let go, man.”

I got the words but not their meaning. Or maybe I did but didn’t want to. “What?” I asked. “Let go man, let go.” he said. Was he a fortune cookie offering some meaningfully meaningless reflection on life? His appearance conveyed no wisdom. Was he joking? His expression conveyed no humour. So how to interpret his words if not from his appearance or expression? Maybe the context can help. He approached me on a dancefloor whilst I was dancing. I reluctantly acknowledged he must be referring to my dancing.

I flopped into a swamp of confusion. Let go?? I hadn’t thought about my arms and legs in ages. I was finally doing the last thing I’d been afraid of doing sober. What else was there to let go of?

In complete contradiction to his advice, I firmly grabbed hold of all that paralyzing self-awareness that I had recently let go of. As I walked to the bar for some water, I tried to remember how normal people walk. They don’t swing their arms like that. Do they put them in their pockets? Or on their hips? No, they do that when they’re standing still. But what, then, do normal people do with their arms when they’re on the move? Oh, yes, they clamp them to their sides like a penguin. And where do normal people put their eyes when they walk? On the floor? But then they can’t see where they’re going. Straight ahead? But then they’ll make contact with other eyes and what happens then? On the ceiling? But then they look like they’re having a spiritual experience when all they want is some water.

How do normal people ever do anything, let alone do it so nonchalantly, when they are constantly confronted by such a complex array of decisions?

I consulted my girlfriend. “Just ignore it. It was a stupid thing to say. It’s not like he was dancing,” she said.

Let go of his “let go”.

But… “Let go, man”. It is the most paradoxical comment. The more I grappled with it, the more I realized I was doing the opposite.

I can’t presume to know what was happening in his head. Perhaps even he can’t. But I will speculate. Maybe he was filled with compassion and a sincere desire to assist his fellow human being. Maybe not.

Maybe he was exhorting me to do the very thing he was unable to do himself, that by highlighting my not letting go, he was able to hide, from himself and others, his own inability to let go. If I dispense advice to let go, my own letting go status is beyond reproach- I clearly know what letting go is all about, so my not letting go is a choice, not a failure. Instead of freezing up and retreating from the dance floor, perhaps I should have just given the same advice to others around me, whispering “let go” into strangers’ ears, thereby proving I know exactly what letting go is all about, even if I’m choosing not to do it in that moment. A bit like the miracle of displaced aggression, when a bitten rat will quickly bite another unrelated rat to make itself feel better. Perhaps this man had recently been advised to let go, and I was serving as an outlet for the pain this advice had inflicted.

In Mexican Masks, Octavio Paz writes:

“we are frightened by other people’s glances, because the body reveals rather than hides our private selves.”

What was I so afraid of my dancing body revealing? The culmination of these fears would be a universal conclusion that, “He is a fucking weirdo.” But could this fear be a self-fulfilling prophesy? So attached to my image in the eyes of the other that I contaminate my image in the eyes of the other. Or is it not possible that dancefloor judgements of a person are ring fenced, and do not extend beyond the dancefloor? Perhaps, just maybe, you can be a bad dancer but a good person… Back to the dance floor. Resentfully. I would not let him win.

Yet now I was confronted with the challenge of letting go of his advice to let go. Apparently “letting go” is a good idea, as any self-help book or blog will tell you. One sensibly advised:

“Take down his pictures; delete his emails from your saved folder… Reward yourself for small acts of acceptance. Get a facial after you delete his number from your phone.”

I yearned to reward myself with a facial, yet I did not have any emails from him or a phone number I could delete. I did not even have any pictures of him I could take down, and nor could I acquire any, because I did not know who he was. I went to Berlin instead.

My brother suggested going to a club. I liked the idea, but the thwarted letting go was still fresh in my mind. Berliners are world leading experts in letting go. Would my holding on be even more starkly exposed by contrast? My brother assured me, “If you feel like you’re being weird in a club in Berlin, there’s always someone nearby doing something ten times weirder.” Indeed, there was something utterly soothing about people scurrying past in gimp masks, trousers left in the cloak room. Conga lines tumbled out of toilet cubicles. Everyone knows drugs dampen inhibitions, but I had never realised you don’t need to be the one taking drugs to experience these benefits. When everyone’s being weird, the self-critic can no longer wield ‘weird’ as a stick to beat you with. There was nothing to let go of.

The arms and the legs were moving, vigorously and pleasurably, but not on my instruction. A friend once told me techno appeals to humans on a primitive level because it evokes the scratches and bangs cavemen used to communicate through cave walls. It seems far-fetched, but who knows. The point is, letting go is less a process of negation, and more a positive process of stepping into, or being stepped into, by the music. The question is: can this liberation generalise? More specifically, can I let go in the absence of gimps? That is one of life’s eternal questions, one we must all confront at some point.

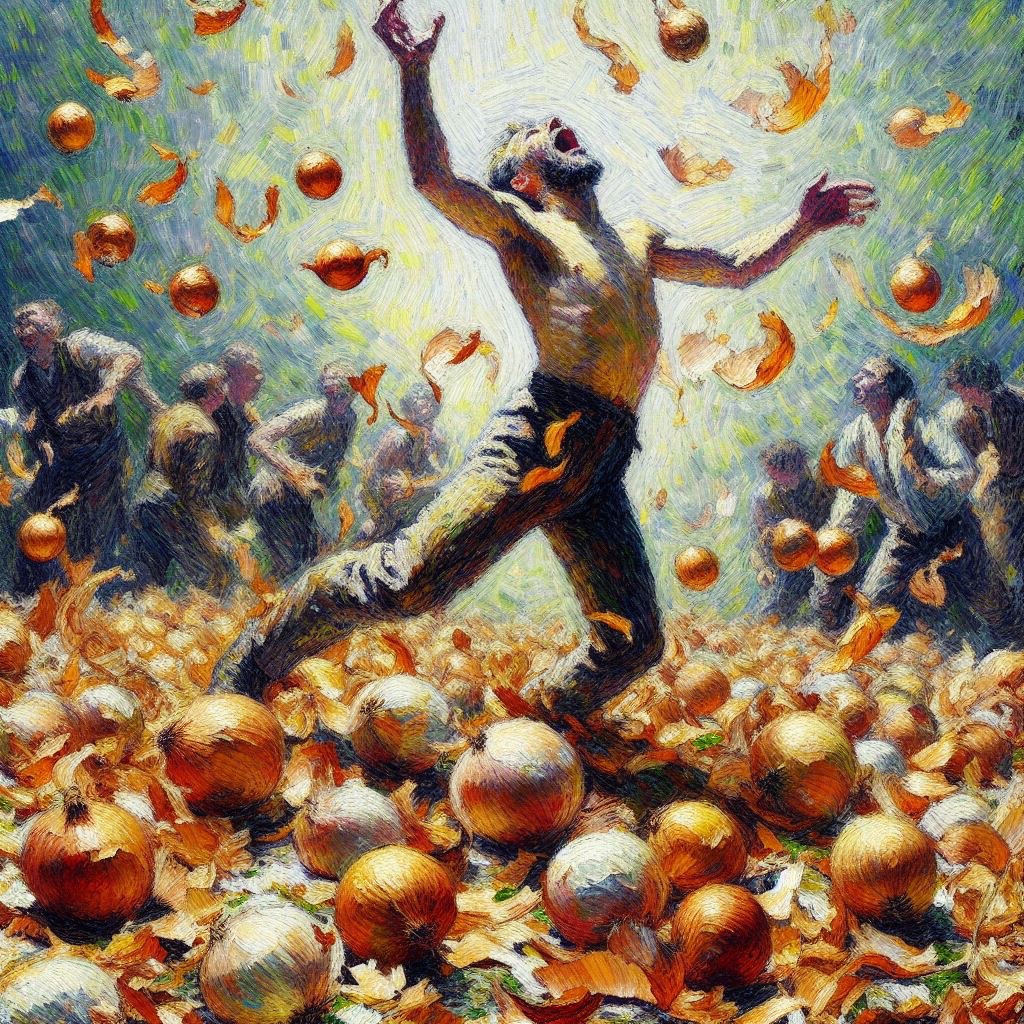

It seems the answer is yes. The general vibe of disinhibition, cultivated in part by the presence of gimps etc., seems to have catalysed something new and lasting. I will be forever grateful to that man who shuffled into my ear with three words, the revelatory meaning of which lay in discovering the absence of their meaning. Keep peeling back the layers of the onion and you are left with nothing. Nothing but an empty pair of hands liberated to dance.